Build Your Skills

Learn music theory Train your ears Track your tempoRead Now

Get the Newsletter

Categories

- | BeatMirror (10)

- | HearEQ (11)

- | Waay (22)

- | WaayFinder (1)

- Audio (16)

- For musicians (34)

- Guitar (2)

- Music theory (15)

- News (42)

- Startup stories (2)

- Tutorial (4)

Keep in Touch

About Ten Kettles

We love music, we love learning, and we love building brand new things. We are Ten Kettles.

Read more >-

December 17, 2021

Sharps or Flats?

Building scales using intervals is one of the fundamental music theory skills you’ll learn in Waay. But there’s a common question that comes up: how do we know when to use a flat (♭)? How do we know when to use a sharp (♯)? And does it matter?

Yes, it does matter! But the good news is that it’s an easy question to answer. We’ll jump right to the “rule of thumb” and then do an example.

The Rule

When building a major scale, natural minor scale, or any of the other modes, remember one thing: don’t skip or repeat any letters. As long as you follow this rule, you’ll pick the right accidental (i.e., sharp or flat) every time.

Example

Let’s start by looking at the F major scale. As you may have learned from Waay, the notes in a scale are separated by a series of whole steps (W) and half-steps (H). For the major scale, that’s W W H W W W H. If you’re unfamiliar with all these Ws and Hs, you’ll see what they mean below!

The scale begins with our root note:

F

To get our second note, we’ll look to the first interval: W W H W W W H. It’s a whole-step (W), which means we go up two notes from F. So that’s F to F♯ and then F♯ to G. The second note of our scale is G! Here’s what we have so far:

F G

The next interval is a whole-step: W W H W W W H. That’s G to G♯ and then G♯ to A. OK, that’s easy enough:

F G A

Now we come to the half-step: W W H W W W H. A half step is just one note up, so we go from A to A♯—which is also called B♭. This is the moment where you need to decide: do you pick the sharp or the flat? A♯ or B♭? Here’s what both choices would look like:

F G A A♯

F G A B♭

Remember our rule: don’t skip or repeat any letters. The first example doesn’t look so good: the letter “A” is repeated! Our rule is broken! But the second example is perfect: each note has its own letter and none are repeated. So we know the right accidental for this scale is a flat.

But… why?

You’ve now learned the rule of thumb—don’t skip or repeat any letters—but why is this so important? Let’s look at a couple reasons.

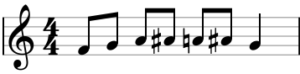

The first reason has to do with sheet music. For sheet music, it gets much more messy (and hard to read) to have a scale that moves between A and A♯ frequently. Here’s what that could look like:

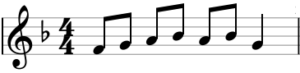

But when each letter just appears once in the scale, then any accidentals can be collected over in the key signature and the music is easier to read.

Secondly, for larger intervals—like the thirds and fifths we learn about in Waay‘s “Chords” course—it makes it simpler if each note in the key has its own letter name. For example, the major third (M3) of D is F♯. Counting up from D, we see that F is the third letter name. So the third interval has the third letter name. Simple!

Summary

So there you have it: when building a major scale (or one of its modes, like the natural minor), don’t skip or repeat any letters and you’ll be sure to use the right accidental.

Any questions or comments? Let me know below or find me at @tenkettles and I’d be happy to help.

NOTE: “Whole-step” can also be called “tone,” and half-step can also be called “semitone.”

Comments